Ambitious climate goals are bringing cities and counties face-to-face with a serious reality: the need for carbon dioxide removal.

Years ago, those concerned about the impacts of climate change were optimistic that reducing greenhouse gas emissions worldwide would be enough to address the problem. That era has passed. We’ve reached a point where carbon dioxide must also be removed from the atmosphere to meet international climate goals, according to the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Although the private sector is spearheading many of the carbon dioxide removal projects currently underway, some U.S. local governments are beginning to consider leading such efforts. A survey of 128 city and county climate action plans revealed that about a third include specific mention of carbon dioxide removal, according to a 2023 report by carbon management firm Carbon Direct and Boulder County, Colorado.

“A growing number of [cities] have discovered that it's not going to be easy to [accomplish net-zero emissions] just through decarbonization,” said Chris Neidl, impact director at Rethinking Removals, a nonprofit that aims to grow the carbon removal industry. “Carbon removal is [a strategy] that the vanguard of those places has already arrived at.”

It’s still a new concept for local governments to be the ones taking the lead on carbon removal projects. Even among the 128 local climate action plans highlighted in Carbon Direct and Boulder County’s report, many describe carbon removal as a secondary benefit of actions that primarily address other issues. Cambridge, Massachusetts, for example, plans to plant trees for shade. The fact that trees suck up and store planet-warming carbon dioxide is a bonus, the report says.

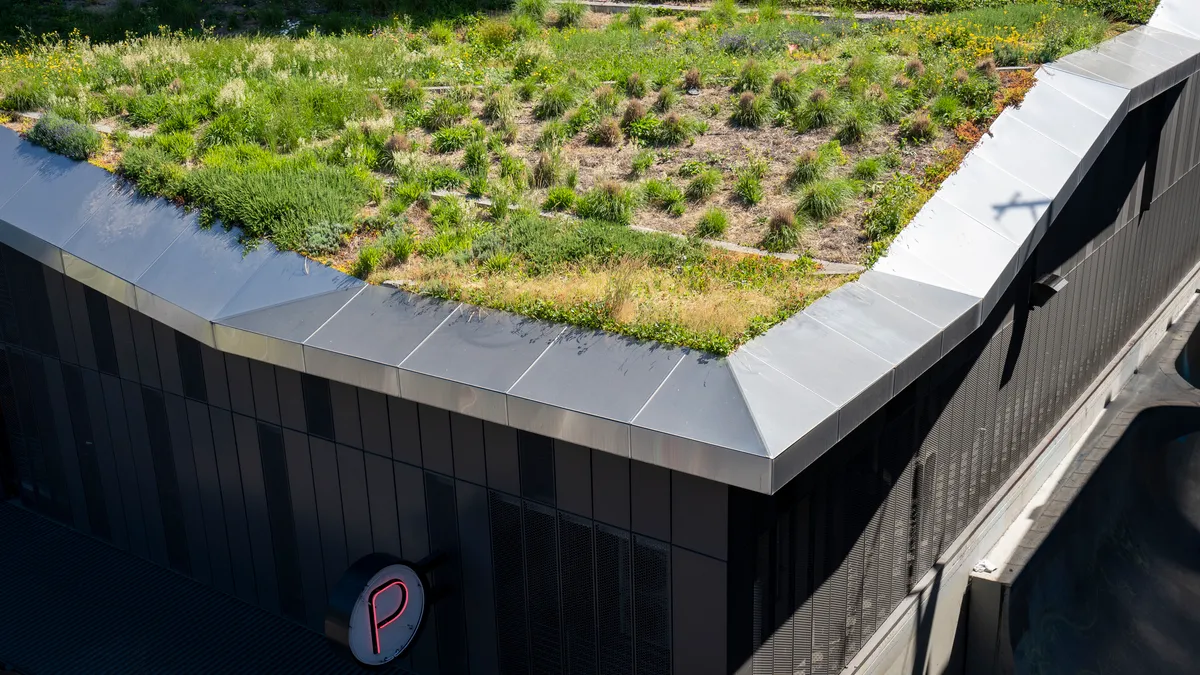

The term carbon removal casts a large net, describing the process of drawing planet-warming carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and storing it for decades, centuries or longer. Carbon removal strategies are usually categorized in two buckets: nature-based solutions like reforestation and technology-based solutions like direct air capture.

“The localities have often focused on nature-based [solutions] because the technology-based are more expensive. There's less known about them,” said Wil Burns, co-director of American University’s Institute for Responsible Carbon Removal.

However, local governments could play a meaningful role in bringing down the cost of the technology by serving as laboratories for testing small-scale projects, he said. “Because the cost is so high, we're not getting sufficient demand for carbon removal,” he said. “But we're not going to get sufficient demand until the costs come down.”

Local projects “can show what doesn't work before we start trying to spend huge amounts of money at the national level,” Burns said. Already, the Biden administration has poured billions of dollars into supporting direct air capture technology.

But carbon removal, especially done with technology-based solutions, is controversial. Critics including scientists and climate advocates worry that it’s a distraction from the unfinished imperative of transitioning off fossil fuels — a concern bolstered by oil companies’ public enthusiasm for carbon removal as a way to continue selling fossil fuels for years to come. Additionally, environmental justice advocates have criticized the fact that some operations for carbon removal projects are sited near neighborhoods long burdened with industrial pollution.

Local carbon removal in practice

Undertaking a carbon removal project can be daunting for local governments that lack the technical expertise, staff and money to “do it right,” Burns said. “There's ways to do [carbon removal] responsibly,” he said, “and there's ways to do it irresponsibly.”

Even seemingly simple nature-based projects must be carefully planned to deliver the intended effect. “If you don't have the capital to maintain those trees, a lot of times those trees die in a couple of years,” Burns said.

Measuring the amount of carbon dioxide such projects remove presents another technical hurdle. “If you can't measure, it didn't happen. That's no overstatement,” Neidl said, noting that measurement, reporting and verification processes are improving.

Burns pointed to Boulder as the type of jurisdiction poised to succeed at carbon removal. “They're backed by a large research university there that does a lot of its own carbon removal,” he said. “The state of Colorado provides resources.”

Boulder County is also a founding member of the 4Corners Carbon Removal Coalition, a network of six local governments in Colorado, Arizona, Utah and New Mexico committed to undertaking locally led carbon removal projects.

Last year, the coalition’s first campaign awarded $390,000 in grants to four local projects that store carbon pulled from the atmosphere in concrete.

In Flagstaff, Arizona, for example, a masonry plant will be retrofitted to capture from the air carbon dioxide, which it will use to cure concrete blocks. A project in Durango, Colorado, will build wall panels from industrial hemp, which removes carbon from the air via photosynthesis faster than any other agricultural rotation crop, according to 4Corners. That project will also store carbon in the form of biochar in cement-like building materials. Biochar is a stable, durable form of carbon created by partially combusting organic matter in the presence of limited oxygen.

Concrete-focused projects have emerged as a promising carbon removal avenue for local governments for several reasons. The process of storing carbon in concrete is well understood, Burns said. Plus, municipalities are some of the largest concrete customers, 4Corners co-founder and Director Ramón Alatorre said. “There are concrete facilities pretty much scattered all over the world, nearby any sort of urban and non-urban space,” he said. “Any projects that we could demonstrate as being able to work at a block facility in Flagstaff, that's inherently replicable.”

Alatorre said that at this early stage, his group is more concerned with projects’ scalability and replicability than how much carbon they individually remove from the atmosphere.

“That said, we want to see good measurement,” he said. “We want high-quality carbon removal, but if it’s a project that's only going to remove less than 1,000 tons of carbon dioxide, that could be fine in terms of wanting to catalyze something that has potential.”

Now, 4Corners is working on a campaign to support projects that leverage what it calls “liability” biomass to remove and durably store carbon from the atmosphere. That biomass can be small trees, branches and other residue that accumulates in overgrown forests or is left by logging operations, or it could be yard waste and municipal organics. Such biomass sources are rich in carbon that has been removed from the air, but without intervention, they soon release carbon back into the atmosphere as they decompose or burn, Alatorre said. The forest residues also pose other risks, he added: They can increase wildfire risk and challenge reforestation efforts.

What’s next for local carbon removal

Carbon removal efforts by municipalities outside of what Burns calls the “usual cast” of communities that are progressive on climate action, like Boulder, “may bode well” for the uptake of locally led carbon removal projects, he said. But it’s not yet clear whether such homegrown efforts will become mainstream, he said.

“A lot of cities are contemplating that carbon removal is going to be part of their net-zero plans,” Burns said. “But I think most of [them are] contemplating they're just going to farm out and buy [carbon] credits.”

For local governments interested in this work, explicitly incorporating carbon removal into net-zero plans “is a really important first step,” Rethinking Removal’s Neidl said. Local and state decision-makers can incorporate environmental justice requirements in carbon removal policy, he added, pointing to a Massachusetts bill that would require state-supported projects to be approved by the director of environmental justice.

A California group is looking to create a model for bringing the community into the development of industrial carbon removal. The Community Alliance for Direct Air Capture — equipped with $3 million in federal funding — plans to work with residents in the San Joaquin Valley to determine whether and how a carbon removal facility should be built in the community. If the project doesn’t gain the community’s support, the coalition has promised to halt it, E&E News reports.

Local governments can also recruit “objective” consultancies, nonprofits or university groups to help manage carbon removal projects, Burns said. “They can help provide some initial guidance to avoid some of the pitfalls.”

As state governments become increasingly savvy on carbon removal, local governments can also look to them for resources, he said.

“You have states like Washington, California, New York and Massachusetts that are increasingly viewing carbon removal as part of their state plans,” he said. “They're contemplating that local governments are going to be partners with them, so they're starting to develop the kind of resources that can help local governments to facilitate those things in a way that's sensible.”