The Belfry Apartments, on the campus of the former Calvary Lutheran Church in Minneapolis, sets its rent at 30% of residents’ income levels, in line with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s definition of affordable housing.

Less and less U.S. rental housing meets that definition. In 2022, a record 22.4 million renter households spent more than 30% of their income on rent and utilities, according to the 2024 “America’s Rental Housing” report by the Joint Center For Housing Studies of Harvard University. The Belfry complex is one example of how a small but growing number of houses of worship are addressing the problem by converting properties they own to affordable housing.

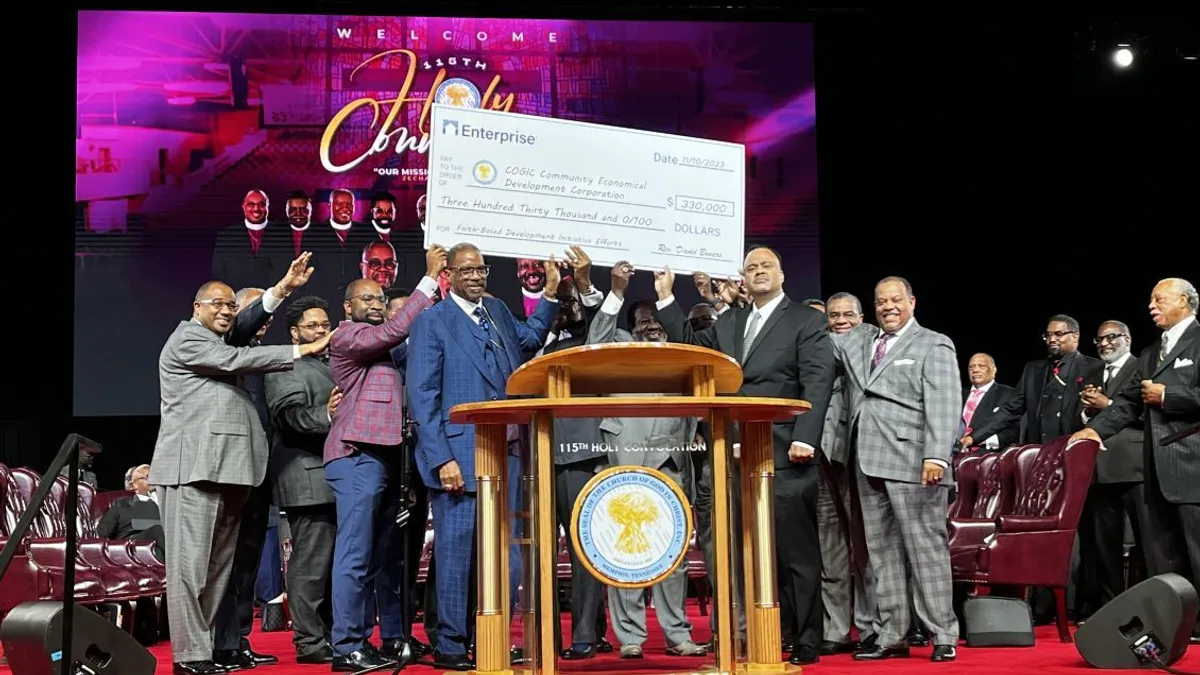

Both the congregations and the communities in which they’re located can benefit from the conversions. “Many houses of worship, although not all, are land-rich and cash-poor,” said the Rev. David Bowers, who founded the Faith-Based Development Initiative within Enterprise Community Partners, a nonprofit focused on addressing the shortage of affordable rental housing. Converting unused or underused property, such as an unneeded parking lot, to affordable housing can help the congregation regain financial solvency while it also pursues its mission of helping those in need, he said.

When providers of affordable housing can acquire church properties at low or no cost, the below-market prices essentially become subsidies that can make affordable housing units more feasible, said Jonathan Kline, associate studio professor in Carnegie Mellon’s School of Architecture. Cities gain affordable housing, as well as the ability to preserve community institutions.

Many of these projects incorporate facilities and services that help the broader community, such as senior centers or educational programs, said attorney Renato Matos, who focuses on the religious and not-for-profit/tax-exempt practice at Capell Barnett Matalon & Schoenfeld, where he’s a managing partner. “These don’t just benefit the church or synagogue,” he adds.

While it’s hard to pinpoint just how many properties owned by the more than 350,000 congregations across the U.S. might be candidates for conversion to housing, a 2023 study from the Terner Center for Housing Innovation that examined the potential in California alone identified more than 47,000 acres of potentially developable land owned by faith-based organizations across the state.

To capture the potential benefits of these conversions, cities may need to assist congregations as they navigate financing challenges, community skepticism and what can seem like a befuddling regulatory environment, experts say.

Bridging the knowledge and trust gap

Successful projects to convert religious institution land to affordable housing often must overcome gaps in both knowledge and trust, Bowers said. Religious leaders, recognizing their lack of real estate expertise, may decide not to act on a potential project rather than risk making mistakes. Conversely, the lack of knowledge can prompt some leaders to take steps that aren’t carefully considered, he said. “Sometimes clergy are seen as easy marks because, almost by definition, they’re a trusting and loving community,” he said.

The knowledge gap can lead to a lack of trust on both sides, Bowers said. Faith leaders might worry about being taken advantage of, while developers might assume church-related projects will take too long and require obtaining agreement from numerous individuals or groups.

FBDI has developed a multiyear cohort model to address these challenges, Bowers said. Leaders from between seven and 15 houses of worship together complete 20 hours of FBDI training on the development process. The cohort members also participate in peer support and sharing — what Bowers calls “iron sharpens iron,” from Proverbs 27:17. Senior clergy members can privately share information and learn from each other about, for instance, different vendors or building regulations.

FBDI has teamed with city agencies and businesses to cover some upfront program costs. For two FBDI cohorts in Washington, D.C., for instance, the D.C. Department of Housing and Community Development provided $1.7 million, the Wells Fargo Foundation added another $1 million, and Enterprise provided $420,000.

The funds cover market studies and feasibility analyses, helping congregations acquire the data they need to make informed “go or no-go” decisions, Bowers said. The money also covers training, development consultants and technical assistance. This funding is key, he notes, because early-stage capital, while minor compared to the project itself, can be difficult to access.

Cities that can streamline the development approval and regulatory process can help facilitate conversions to affordable housing. In some municipalities, projects may need approval from more than a dozen agencies, which can extend the timeline for planning, permitting and construction to multiple years, said Brett Theodos, senior fellow and director of the Community Economic Development Hub at the Urban Institute.

NIMBYism and other barriers

Community opposition to new affordable housing developments can take on a different flavor when a house of worship is involved.

Older religious structures often are culturally significant to communities in which they’re located. “The memories might go back generations,” Kline said. Radical changes might feel traumatic if they’re not done carefully, he said.

Cities want to find ways to help communities become comfortable with the changes, Kline said. A big part of this is how the decisions to proceed are made, he said.

A house of worship that’s been in a neighborhood for a while, even a beloved institution, can become a target for opposition to its conversion to housing simply because of its longevity, Bowers said. For instance, some residents might not have agreed with a change the organization made years ago and voice their frustration when a new project is proposed. “It can add an overlay to things,” he said.

To head off problems later, such as disagreements about how monetary reserves are handled or how tenants are identified and prices set, these projects need a clear ownership structure, Theodos said. For instance, which parts of the property will the church continue to own? Who will own the land?

A historic designation, such as inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places, can both facilitate and hinder development, Kline said. In some areas, buildings with a historic designation or within a historic district might qualify for tax benefits or grants. Yet because the designation is designed to encourage historic preservation, it can be difficult to radically convert these properties, Kline said.

Cities will want to carefully consider such designations, Matos said. For instance, a congregation that has dwindled to a few dozen members likely won’t be able to maintain its building to landmark standards, he said.

Last year, California passed the Affordable Housing on Faith Lands Act — also called the “Yes in God’s Back Yard Bill” — which allows faith-based institutions and nonprofit colleges to build affordable housing on their property even if local zoning forbids it. The bill’s sponsor, state Sen. Scott Wiener, called the law a “game-changer,” saying it will open up 170,000 acres of land in California for affordable housing.

Speaking about the trend of religious institution-to-affordable housing conversions more generally, Theodos said that no single project will solve the housing affordability crisis. “However, cumulatively they add up.”