Communities will pay the price as Federal Emergency Management Agency staff and funding are cut, shifting the burden of disaster preparation and response to cities and states, a panel of former FEMA and U.S. Forest Service officials warned during a panel discussion last week about the impact of FEMA cuts and the agency’s potential elimination.

“We’re going to have the potential to lose lives and property and see towns and small governments going broke,” Bobbie Scopa, a retired firefighter with the U.S. Forest Service, said.

In addition to losing on-the-ground emergency response staff, FEMA is losing the people who handle critical financial and coordination issues during and after emergencies, Scopa said. She’s particularly concerned about small communities that “aren’t really robust financially to begin with.”

“This is going to [have] a cumulative effect on them,” she said. “We start impacting their grants. We start impacting the ability to reimburse them for costs. We reduce the amount of response that we have available for them … from the federal government.”

The disaster response cycle already “starts local and ends local,” said Tom Sivak, a former FEMA administrator, now chief emergency manager for EM1. “At the local level, these responders are in the fight from the moment that incident takes place until that long-term recovery process — which may last years — ends.”

Smaller communities often lack the “capacity and capability” to respond throughout the process, Sivak said. FEMA provides expertise, statutory authority, resources — “aka, money” — and it knows how to coordinate federal, state and local agencies, he added.

“We’ve got a system, and FEMA is the framework,” Scopa said. If FEMA is eliminated or replaced with a new agency, response teams will have to reinvent the process, she said. “It’d be the ultimate in inefficiency, and if it gets decentralized, then it’s not going to get done.”

Riva Duncan, a retired firefighter and consultant for the U.S. Forest Service, is already seeing the impacts of staff cuts. She said she had just returned from volunteering to help fight wildfires in New Mexico, where no one was available to process fire management assistance grants for the affected communities. That delays reimbursements to states, which causes a cascade of problems, she said.

“We’re looking at pretty serious consequences because then what do they do for the next fire?” she said. “This is all integrated. It’s like this web where we support each other, we rely on each other. We’re all a little concerned about what the rest of the wildland fire season looks like.”

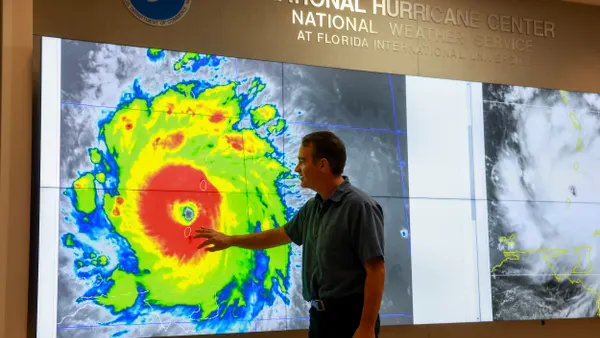

As natural disasters have proliferated over the past decade — the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration reported 27 with losses exceeding $1 billion in 2024 — Sivak said FEMA has been in “a perpetual state of response,” so cutbacks now could have devastating consequences.

“As far forward as we’ve come, we’re kicking ourselves back, who knows how long, and the challenge that we’re going to face is that some communities are going to be lost,” he said. “We know that sea level rise is a thing. We know that there’s communities that have to have managed retreat because they’re flooding at a record rate.”

Eliminating FEMA, even it were subsumed into another federal agency, “means that we will be taking [away] that focus of disaster, consequence management, crisis management, emergency management and built resilience … where FEMA has put a lot of time and attention, especially over the disasters of the last 25 years,” Sivak said. “Once that goes away, how are we going to get it back?

Editor’s note: We have updated this article to correct the name of the Federal Emergency Management Agency.