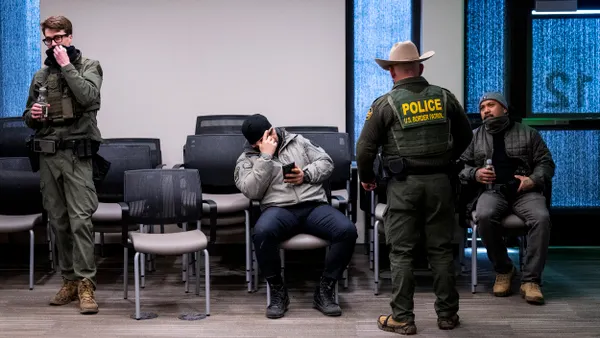

Responding to “a disturbing rise in rhetoric from political and community leaders” that it says is contributing to violence against law enforcement officers, elected officials and the public, the International Association of Chiefs of Police published a resolution condemning the incitement of violence earlier this month.

Acts of violence are “often calculated, fueled by hatred, and emboldened by the toxic rhetoric that has become far too common in public discourse, particularly on social media, talk radio, and other media platforms,” the resolution states. It condemns speech that legitimizes or incites violence, supports efforts to educate leaders and the public on the importance of maintaining civil discourse and reaffirms the association’s commitment to defending the principles of justice and democracy.

“We have the ability to be the adults in the room,” said Drew Evans, superintendent of the Minnesota Department of Public Safety’s Bureau of Criminal Apprehension, during the IACP’s annual conference in Denver Monday. Evans was part of a panel of law enforcement leaders who have seen heinous acts of political violence firsthand — from the Capitol uprising on Jan. 6, 2021, to the assassination of Minnesota House Speaker Melissa Hortman and her husband. The panelists shared advice on carrying out that resolution.

Apolitical leadership in a polarized nation

“As law enforcement, we have the ability to take that temperature down, to stay focused on what’s important, to recognize what’s important for all of our communities,” Evans said. Calling law enforcement the nation’s most visible and stabilizing force, Evans said officers “have to be apolitical. … The law enforcement profession doesn’t serve one party or the other. We serve all citizens.”

In the immediate aftermath of the Hortmans’ murder, Evans said his team received information on the killer’s motivation. He credits elected officials in Minnesota for steering the conversation away from that, saying that bringing in politics would have made the situation untenable for everyone. “It’s easy to blame that one set of people rather than the evil acts of this individual and what they did,” he said.

Tom Manger, who recently retired as chief of the U.S. Capitol Police, said the first call law enforcement officers often receive after an incident is from elected officials wanting to know the perpetrator’s motivation. “All they want to do is figure out, well, which side were they on?” he said. It “doesn’t matter which side they’re on. There are plenty of people that have been radicalized on both extremes.”

Politicians need to tone down their rhetoric, Manger said, though he’s not sure “how we ever put the horse back in the barn” regarding the divisive influence of social media and the online radicalization of people. Law enforcement agencies need to add staff positions to address those threats, he said.

The Capitol Police has “profoundly expanded the number of people who were investigating threats” and added criminal researchers and intelligence analysts to do prevention work in recent years, Manger said. And while conceding that not every agency has the budget to hire a team of researchers and analysts, Manger said just one staff member with access to databases and the ability to scour the internet for threats can go a long way.

“You’ve got to have folks working on this, looking at this, to try and see what’s brewing before something happens,” Manger said.

Lead with optimism in cynical times

In Los Angeles, Police Chief Jim McDonnell said his team is vigilant about keeping up with online threats. His agency might not have adequate resources for high-risk or high-profile events that could be targeted for violence, he said. That’s why it’s important for it to work closely with other agencies in his region as well as federal, state and local partners.

It’s also incumbent on every law enforcement officer to be a positive voice in a sea of negativity, McDonnell said. If officers succumb to negativity and hopelessness, they won’t perform at the levels they need to keep themselves safe and serve their communities, he said.

“Each one of us are leaders in our community,” McDonnell said. “We have an ability to be able to be different than all of the others, to be positive when other people are negative, to be that shining light.”

The same tactics that work to de-escalate situations on the street can work in political environments, McDonnell said. “We owe it to [our communities] to be positive, to be strong, to be measured in our approach.”

Former New Orleans Police Superintendent Ronal Serpas, now a criminology and justice professor at Loyola University in New Orleans, said it is law enforcement leaders’ duty to help the next generation. “Reach out, talk to people, help them through this time. This is a tough time for them, but we can all work together and get through.”