For Smart Growth, Not All Urban Density is Created Equal

Have you ever noticed how those of us who promote walkable, "smart growth" city neighborhoods often choose historic districts to illustrate what we advocate? Take the photo at the top of this article, for example: I'm not sure what city it is from, but it clearly is a historic neighborhood. It was chosen by the advocacy group Smart Growth America to illustrate the group's recent tweet "Healthy, diverse smart growth neighborhoods attract talent, commerce, and investment."

When they look like that, they certainly do. A highly detailed study published earlier this year (and reported here) by the National Trust for Historic Preservation demonstrated that, compared to districts dominated by larger, newer buildings, those with smaller and older buildings were found to score better on multiple measures of urban vitality.

Below is another example of an older neighborhood being used to illustrate smart growth principles. It's a classic "Main Street" from Rochester, Michigan, and it appears at the top of Smart Growth America's Twitter home page:

We use examples like these to illustrate our advocacy because they represent many of the qualities that newer suburban sprawl lacks but that we would like to see in more urban and suburban neighborhoods: walkability, density, and a diverse mix of uses, to name three.

But I think there's more going on than that. We show these neighborhoods because we know people will like them and, we believe, associate them favorably our cause, in effect thinking, "this smart growth stuff is pretty attractive." And I submit that a huge reason why people feel attracted to and comfortable in historic neighborhoods is not just because of their familiarity and walkability but also because they present urban density at a human scale.

Note, for example, how the second photo, the one of Rochester, shows mostly two-story buildings. The one at the top shows a mix of building sizes ranging from two stories up to what looks like about six stories for the tallest buildings.

The great Danish architect and walkability guru Jan Gehl would likely conclude that the building heights shown in the two photos are about right to optimize the pedestrian experience. After extensive study of how humans behave in different kinds of environments, Gehl has concluded that the most comfortable building height for urban pedestrians is between 12.5 and 25 meters, or about three to six stories. (See the excellent discussion in Li Teng, Human Scale Development, Master's thesis, Blekinge Tekniska Hogskola.) Could that be part of why people love these historic city districts so much?

I'm not going to argue that we should never build above five or six stories (although some architects do). I can go higher, especially in the right context. But I do think that, in their passion for the highest possible densities as an antidote to low-density sprawl, too many urbanist advocates overlook the considerable benefits of still-relatively-high city density at a human scale.

Indeed, consider the environmental benefits of density, which has been shown to reduce the amount of runoff-causing impervious surface in watersheds (because of the huge amount of transportation-related pavement required to serve sprawl) as well as reduce driving rates per capita, compared to sprawl. I'm going to try to avoid getting overly tech-y about it here, but the research shows that these benefits are found mostly at the lower end of the density spectrum; the environmental gains begin to diminish at a density of about 20 homes per acre, and there is little additional benefit to these indicators as density increases beyond about 60 homes per acre.

Although we can achieve a density of 60 homes per acre by building high rises, we can also do so by building to the dimensions of a historic district similar to the one shown in Smart Growth America's tweet and at the top of this article. My friend Susan Henderson, an urban planner, calculated the density of the neighborhood around Boston's Louisburg Square, shown just above, at about 53 homes per acre.

The good news is that there are some terrific examples of recently built urban, smart growth development assembled at a human scale similar to that of well-liked historic neighborhoods. Two of my favorites are shown above. First, Fruitvale Village in Oakland, California, is a mixed-use, mixed-income, transit-oriented development built next to a BART station. It's mostly three and four stories tall and, importantly, modulated in its dimensions so that pedestrians enjoy a variety of facades and sight distances. I visited a few years ago and found it delightful.

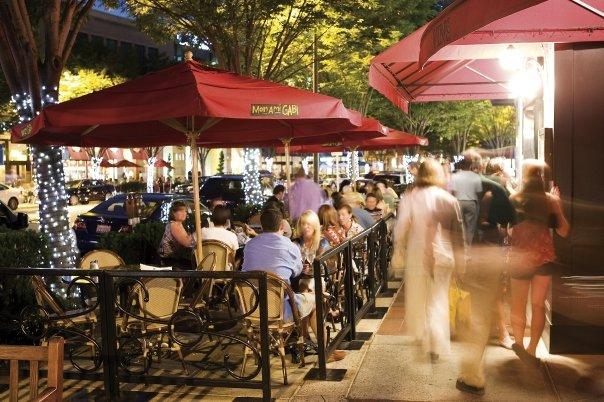

Pictured just below Fruitvale (and again below) is my favorite newer neighborhood development in the DC area, the terrific Bethesda Row in suburban Maryland. It's more traditionally styled than Fruitvale, and much more East Coast in its red-brick appearance but it, too, is mixed-use, highly walkable, and transit-accessible, with a Metro station about three blocks away. It's also on the Capital Crescent Trail, one of the region's most popular bicycling and walking routes. I like to think that Jan Gehl would approve: building heights in Bethesda Row range from two to about six stories. It is immensely popular with people, who fill its shops, cafes and plazas at all hours.

The development is not admired by all smart growth advocates, however. One professional friend told me at a recent meeting that she thought Bethesda Row was "an inefficient use of land," particularly objecting to its two-story portions (which are built to a scale and style very similar to the "Main Street" in Rochester, depicted on Smart Growth America's Twitter page). Personally, I think it is average density that counts and, so long as lower-density portions are complemented by higher-density portions elsewhere in the development, they add interest, daylight, and a scale that humans find appealing. I remember the automobile-oriented wasteland that was the Bethesda Row site before the current development was built; the improvement is immense.

Today's Bethesda has plenty of high-rise buildings. What it needs are more mixed-use, highly walkable projects that serve as great ambassadors for human-scaled urban density, in the same way that the historic neighborhoods chosen by Smart Growth America do. Bethesda Row has been highlighted as an outstanding example of smart growth on the web site of the US Environmental Protection Agency. It has also won awards from the Washington area Smart Growth Alliance, the Urban Land Institute, the Congress for the New Urbanism, and the Urban Land Institute.

Unfortunately, a lot of what is being built in the name of smart growth these days is far less human-scaled and, to my eye, far less appealing. You are highly unlikely to see the new buildings just above, for example, featured as feel-good ambassadors for smart growth on the website of a leading advocacy organization. These organizations' communications people know better than to trot out exactly what many people fear being built in their neighborhoods.

I'll grant that it is not impossible to build appealing high-rises that bring benefits to urban neighborhoods and the planet as well as to developers and tenants. (Berlin's Sony Center and Fukuoka, Japan's ACROS Building come to mind.) But, personally, I fail to see why we should be supporting density for its own sake. Smart growth and environmental advocates should be demanding more, and we should remember that we usually sell our ideas with images of human-scaled developments for a reason. They work for people as well as for ideology.

Move your cursor over the images for credit information.