Broward County, Florida, developed a $29 billion resilience plan funded by public and private interests in a four-year process. Next door, Dade County, Florida, is requiring every infrastructure project in the county to sign an attestation that managers considered sea level rise during design and planning. In Raleigh, North Carolina, city officials are working with UN-Habitat to plant trees to mitigate urban heat islands.

These are some of the strategies experts and city leaders at Smart Cities World’s Cities Climate Action Summit shared for dealing with rising sea levels, rain bombs, hurricanes and heat waves. As extreme weather events grow more frequent and intense, cities are turning to resilient design, integrated urban planning, nature-based solutions and AI to bolster their infrastructure and protect residents.

Corinne LeTourneau, founding principal of Resilient Cities Catalyst, said she has partnered with 78 cities and regions in the past five years to accelerate climate resilience action. “Every single one of those cities, communities and regions is grappling with the impacts of extreme weather,” she said. “They’re feeling it in their daily lives.”

Speakers identified three key elements in their resilience planning and implementation.

Data

In 2023, Broward County was in the midst of its resilience planning when 26 inches of rain fell on Fort Lauderdale in less than 24 hours, damaging more than 1,000 structures. “It was unbelievable,” said County Mayor Beam Furr. “It was so deep, so quick.”

County officials were able to gather valuable data on the record-setting flood from the sensors that were in place for the resilience plan’s modeling. That data indicated the county would have to “reconsider our entire capacity” for flood control, Furr said.

“The price tag is huge, though,” Furr added, and the hardest part is getting people to accept the cost. “How do we show the urgency of it? Well, that flood showed the urgency of it very quickly. So, it’s allowed us to quickly bring in the business sector and say, ‘Look, we need to do this now, or you’re going to have property values plummet.’”

Data is a crucial element in persuading policy makers and the public to invest in resiliency efforts, said Eleni Myrivili, global chief heat officer for UN-Habitat. One of the best tools she’s found for convincing officials to invest in urban green space is a report showing that cities with a tree canopy of 30% or more can lower deaths linked to extreme heat by a third.

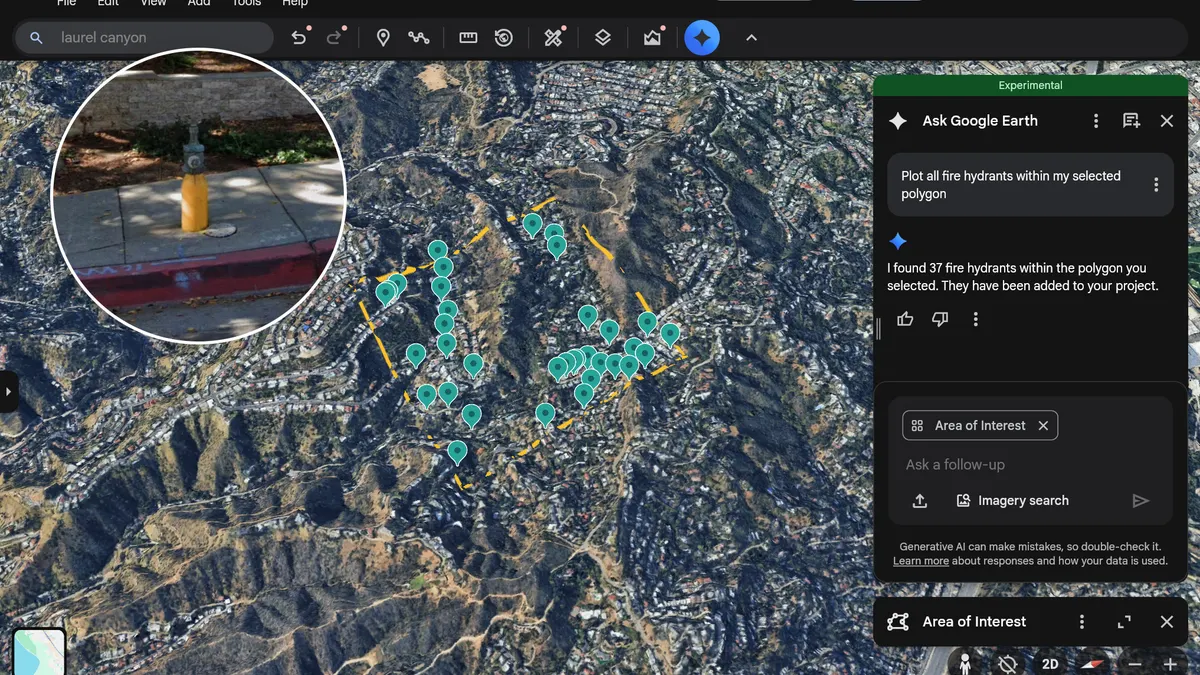

AI is making it easier to collect and analyze that data, bringing down the cost of modeling while increasing its resolution, said Koki Mashita, co-founder and CEO of Aeolus Labs, which he described as a team of theoretical physicists and machine learning engineers building “the world’s first infrastructure to defend ourselves from extreme weather.”

Machine learning makes it easy to map resilience projects’ impact, which Mashita said is “fundamentally very important, especially when you’re trying to get a pretty large project to go through, because people have no idea what the potential impacts, what the positive outcome could be.”

Modeling “creates a much more convincing narrative,” he said.

Cross-department coordination

Perhaps an even greater challenge than funding resilience plans is implementing them, LeTourneau said. “Cities are set up for 20th-century problems, and adapting to meet those challenges means you have to overcome these deeply ingrained silos.”

Every department that would touch a resilience plan must be aligned on its goals and vision so they can co-design and implement their priorities together.

“That sounds simple,” LeTourneau said. “It is not.”

Too often, city officials will agree on a resilience plan, then everyone will believe it’s someone else’s responsibility to implement it, she said.

In Miami-Dade County, “it’s taken a really bold vision and leadership from our mayor to operationalize resilience across all our department and the departments that are in contact with the community,” said Julie Dick, deputy chief resilience officer. “Through emergency management or through housing and community services or transit and public works, all of these different components and tentacles of county government have to have resilience integrated into their DNA and into how they’re working and communicating with the public.”

LeTourneau points to Austin, Texas, as another city that established a shared vision and clear priorities using what she called the “planning while doing approach.” Austin’s biggest resilience challenge is extreme heat, so Resilient Cities Catalyst helped city officials develop a cross-departmental heat resilience playbook for one neighborhood to prove the approach could have an impact.

“That kind of model shows how a clear framework, paired with strong collaboration from the community, all the city departments, and then the technical support needed, can help rapidly translate and address that challenge of how you get from planning to implementation,” LeTourneau said.

Community engagement

“It’s deeply difficult to align across departments, but you also have to meaningfully engage community members whose lives are directly impacted by that extreme weather,” LeTourneau said. “It doesn’t just mean you have to have all the departments at the table, but how do you have the community at the table?”

Education and communication campaigns are key to overcoming both policymaker and taxpayer resistance to investing in long-term resilience solutions like urban forests, said Myrivili.

Those are “probably the most important tool that we have to address extreme heat,” she said, and to break through complacency. “There’s kind of a feeling that it’s always been hot. We’ve had rain before.”