Democrats in the U.S. House of Representatives are expected to pass the Inflation Reduction Act today. Unlike the earlier $3.5 trillion Build Back Better bill, the new climate and healthcare bill — which passed through the Senate along party lines on Sunday — does not include any new funding to expand the nation’s housing stock or expand rental assistance to low-income people.

Without an influx of federal funds to help, cities and states are left to find their own solutions to help low-income renters who may face eviction or income discrimination.

Smart Cities Dive spoke with Carl Gershenson, project director at The Eviction Lab at Princeton University about a number of ways that cities and states could help. These are seven of his ideas:

1. Implement eviction diversion programs: When evictions go to housing court, tenants are often at a disadvantage relative to their landlords. An eviction filing reaching the court system can also have a permanent effect on a tenant’s ability to obtain future housing since a landlord can see that information during the application process, said Gershenson.

Eviction diversion programs, like the one in Philadelphia, attempt to resolve landlord-tenant disputes without reaching the courts. Diversion programs can be “pretty successful” at resolving such disputes, especially when trained mediators, wrap-around services, financial counseling, and sometimes even emergency rental assistance are available, said Gershenson. These programs will not solve all eviction cases, but when landlords and tenants are both willing to enter into it, “you can get really great outcomes,” he added.

2. Leverage Emergency Rental Assistance: While the IRA does not provide additional funding that expands rental assistance, some cities and states are sitting on a lot of American Rescue Plan Act money that could be used for that purpose. “There’s nothing more effective than money,” said Gershenson.

3. Modify qualified allocation plans: The criteria that cities and states use to distribute low-income housing tax credits — tax credits for developers building or rehabbing low-income housing — are called qualified allocation plans (QAP). Gershenson said most QAPs do not mention eviction or renter stability as a goal for receiving low-income housing tax credits. Cities could lobby their state to modify its QAP to favor developers that opt into eviction diversion programs or provide “some kind of [good cause] eviction guarantee.” Cities that are able to set their own QAP could write that in themselves. “This is a lever that basically no states or cities have been using to reduce eviction rates,” he said.

4. Collect better eviction data: There has been an improvement on this front in recent years, but cities and states should collect eviction data and make it publicly available in a way that protects renters’ privacy but also allows people to see which landlords have filed the most evictions, he said. In some cities, a large share of the evictions are filed by the same handful of landlords.

“There are some bad actors out there who are really exacerbating the eviction crisis in their communities and naming and shaming is one way to address this,” said Gershenson. “But then if you know who these are, it is possible for city council and city administrations to find some way to crack down on that abusive behavior.”

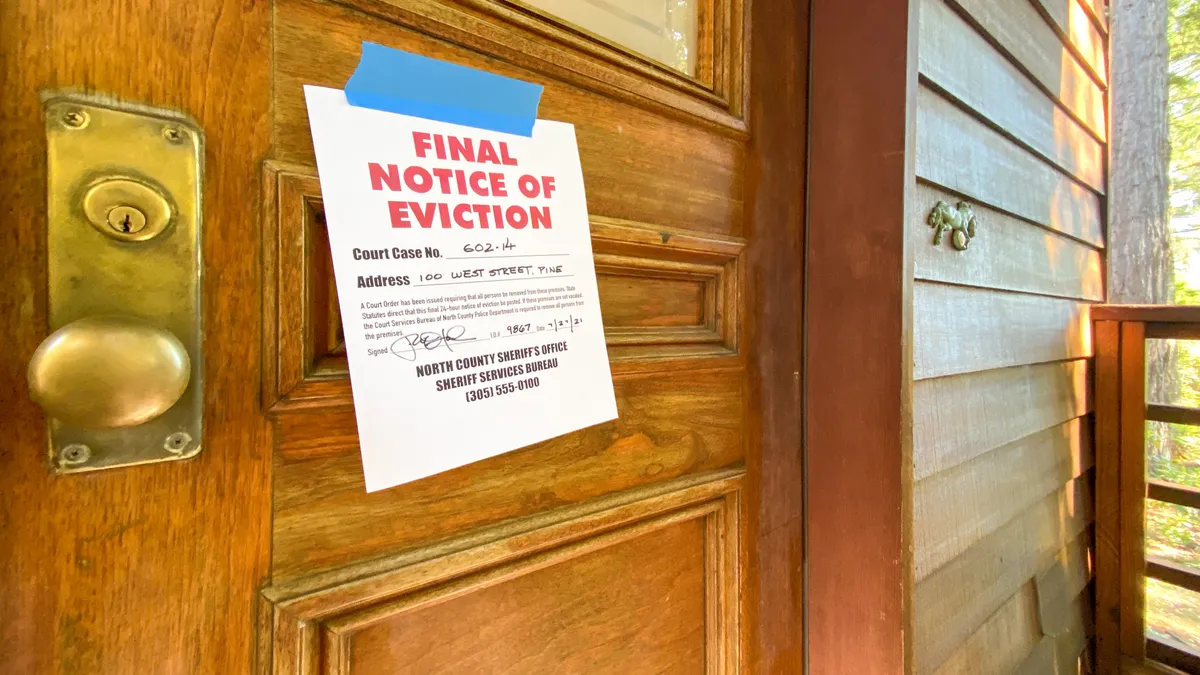

5. Give tenants more time after receiving an eviction notice: In most jurisdictions, if a tenant is late on rent, even if it’s a small amount, a landlord has the right to evict, said Gershenson. Even in cities where a tenant can avoid eviction by paying the amount owed before the eviction is executed, if the sheriff shows up before the tenant can pay the full amount of the arrears, that renter has no other recourse, he said. Giving a tenant more notice that eviction has been filed or will be filed against them, he said, could give that renter the time they need to find the money to pay off the back rent and stay. “It’s a very simple thing, just giving people more time to breathe,” he said.

6. Allow evicted tenants to seal their records: Finding housing as a renter can be difficult. The challenge is even harder when a tenant has an eviction mark on their screening report, said Gershenson. Some cities are finding ways to allow tenants to seal their records, especially if their case has been dismissed or resolved in their favor, he said. Still, those laws can often be inadequate because tenant screening companies are constantly scraping court dockets — potentially marking someone as having been evicted, even if their case was dismissed.

There are ways cities can get around that issue. For instance, Philadelphia’s Renters’ Access Act allows tenants to ask for the criteria the landlord used to deny them housing and, if needed, correct inaccurate information on a screening report. But, “that assumes a fair amount of savvy on the part of the tenant” to ask for that information or know that the protections even exist, said Gershenson. Cities with an active legal services community can walk tenants through it and train large property managers not to abuse those screening reports, he said.

7. Expand the housing stock: There is a massive shortage of housing throughout the U.S. Building new housing developments can be difficult and costly because of long and complex approval processes by local governments.

As such, affordable housing projects that are located near transit can really help lower-income tenants, said Gershenson. But even in cities where there are robust tenant protections, proving income discrimination when a person who has a rental assistance voucher has been denied can be challenging when there are multiple applicants for the same unit, a scenario that’s worsened whenever the market is tighter.

“When you have such a tight market, this really allows landlords to exercise their discretion in whatever manner they want and that often means exercising it in a way that is really tough on the least advantaged renters,” said Gershenson.