Dive Brief:

- Because of political and economic disruption at the state and federal level and expanding use of AI and other technologies, cities will need to augment traditional, vertical silo operations with more horizontal, mesh-oriented models, a panel of experts said during a Jan. 7 Bloomberg Center for Cities at Harvard University panel about how successful cities will operate in the 2030s.

- To achieve this, the experts said, cities will need to invest in training employees to develop new mindsets and skills.

- “Cities are playing an increasingly important role all over the world … perhaps as national governments are going a bit crazy sometimes,” said Geoff Mulgan, professor of collective intelligence, public policy and social innovation at University College London. “Mayors are filling the space and are highly active on everything from housing to climate change to poverty.”

Dive Insight:

Traditionally, cities are organized into silos, with departments and agencies that protect their turf and don’t often interact, Mulgan said.

Tasks like lowering bus fares are “a very efficient way of concentrating power, expertise, capability and accountability,” he said. “But as I think we all know, most issues cut across those silos, and so there's a new sort of language of tools, of how you create shared budgets or targets or appointments or data or teams.”

Mulgan said cities of the future will need to rely on operations that are more of a mesh, like the worldwide web concept that’s the basis of the internet.

He cited examples of what mesh thinking would look like:

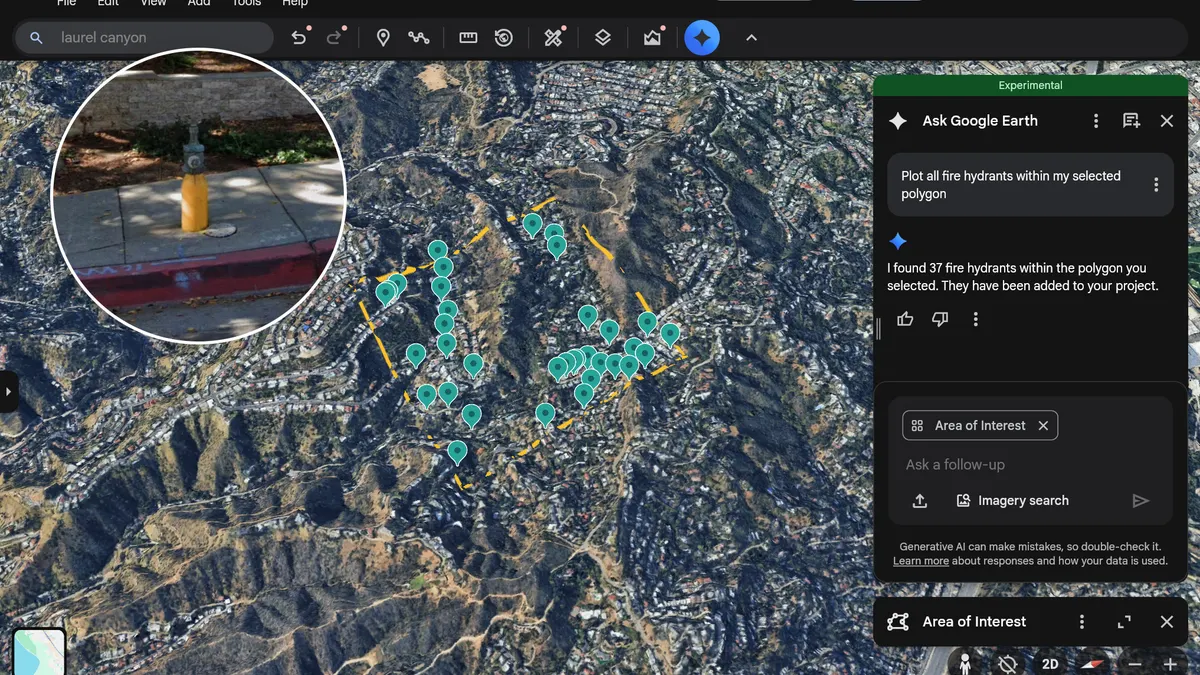

- Standardized, simplified digital platforms to make it easier for residents and businesses to access city services.

- Tools to help cities harness the brainpower of academics and residents.

- Integrated services and care blocks to address related issues like senior services, health care and housing.

- New positions like “chief heat officers” to deal with climate change.

- Tools that address affordability issues, like India’s open network models that enable residents to compare prices on services like ride sharing and software design offered by entrepreneurs and small businesses.

In Atlanta, Mayor Andre Dickens is using horizontal, mesh-like city structures to address his goal of creating 20,000 affordable housing units, said Bruce Katz, co-founder of New Localism Advisors and a visiting professor at the London School of Economics.

Katz said Dickens’ goal includes building housing and acquiring and preserving existing housing, which involves stakeholders like homeowners, developers and entities such as school districts that own large pieces of land.

Dickens “basically centralizes some power in the mayor's office, brings in a new team. And then they begin to meet week by week — not to talk about housing policy in general, but to talk about delivering projects. So, you go from the abstract to the specific pretty damn fast,” Katz said. “It’s a combination of a really focused exercise of authority or power, combined with a much more inclusive and comprehensive set of actors working together, and figuring out how that works in a local context.”

To make shifts like this, city employees will need to develop mindsets and skills to work in new ways, said Beth Simone Noveck, director of Northeastern University’s Burnes Center for Social Change and chief AI strategist for New Jersey.

“As we talk about using new tools or new methods, whether it's human-centered design, whether it's new forms of collective intelligence building, whether it's using AI, we have to teach people how to use these skills. That's something we do regularly in the private sector,” but not in city government, she said.

Correction: This article was updated to indicate the event was a panel discussion, update the link to the video and include Beth Simone Noveck's full name.