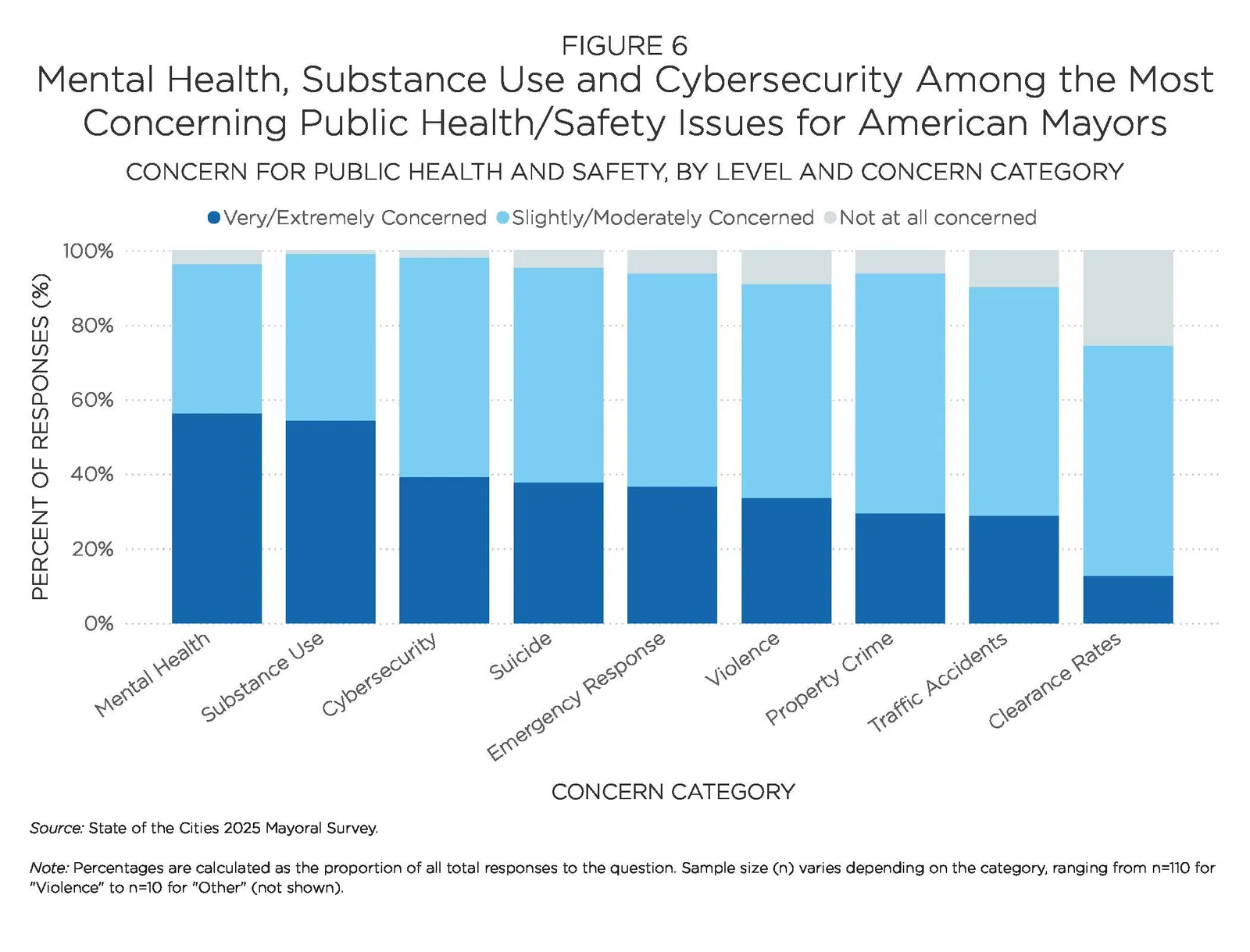

City leaders are taking a more holistic approach to community well-being, recognizing that public safety and public health are interconnected. They are addressing the importance of enforcing laws at the same time they are dealing with the root causes of crime, the National League of Cities’ State of the Cities 2025 report found.

NLC researchers surveyed 238 mayors and analyzed 53 mayoral “state of the city” speeches during the first quarter of 2025 for the report. They found that public health and safety is mayors’ second-highest priority after economic development, and significant concerns around mental health, suicide and substance abuse dominate public health and safety discussions. Nearly all — 99% — of survey respondents said they’re concerned about substance abuse, and 96% are concerned about suicide.

“The suicide piece is something we haven’t quite gotten our heads around yet,” said NLC Research Director Christine Baker-Smith. “It looks like it may be coming from continued and growing concerns around mental health.”

During an event to introduce the report last week, NLC President and Athens, Ohio, Mayor Steve Patterson said mental health is a national crisis and urged city leaders to “be mindful of your own mental health as we’re watching and tracking what we need to do in communities to help people struggling with mental health.”

“Economic development, public safety, public health, mental health, homelessness, substance abuse – all of those things are attached,” Riakos Adams, mayor pro tem of Killeen, Texas, said during the event.

“If you only focus on one,” he said, “it’s unbalanced.” Adams said his city is determining how to allocate resources for a more holistic approach to those issues.

The intersection of public health and public safety “captures everything that’s happening in a city,” Baker-Smith said. “Instead of [saying], yes, this is just about property crime or yes, this is just about substance abuse, it’s like, oh, these are all interrelated.”

Ivonne Montes Diaz, NLC’s program manager for research and data and the lead author of the report, said her analysis of the mayoral speeches indicates they “really want to create holistic approaches” to this crisis.

Mayors are “not just addressing crime,” Baker-Smith said. “They’re trying to rethink their police force as a wraparound public safety force, which I think is really exciting.”

More than a quarter of survey respondents told NLC they’ve implemented alternative crisis co-response teams in which law enforcement and clinicians work together during calls involving a behavioral health crisis, Montes Diaz said. This focus on de-escalation and behavioral health services in a “people-centric approach to crises of mental health, substance abuse disorder, homelessness and more” can “ease the burden on law enforcement,” the report states.

Sending mental health professionals on nonviolent calls is a positive step, Baker-Smith said, but there are hurdles to overcome. The public safety, nursing and mental health professions are all dealing with workforce shortages, she said, and because there is no approved training model for these types of calls, every city is doing it differently.

Another obstacle is that only large and midsize cities have their own law enforcement departments; smaller cities rely on county sheriffs, Baker-Smith said. Public health is usually managed by the county as well.

“As a local leader, if you have public safety provided by the county, you have to not just convince your city, you have to convince the county and all the surrounding cities to agree to this model,” she said. “It requires collaboration between the city and the county, which is doable but adds another layer of challenge.