A federal judge’s two-week temporary restraining order preventing the Trump administration from freezing over $10 billion in family assistance funding in five states is set to expire Friday, leaving local governments and aid organizations grappling with an uncertain financial future.

There has been “quite a lot of chaos and fear about what the funding freeze would mean in Minnesota,” one of the states where funding is set to expire, said Clare Sanford, vice president of government relations for the Minnesota Child Care Association.

The temporary restraining order followed a lawsuit filed Jan. 8 by California, Colorado, Illinois, Minnesota and New York in response to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Jan. 6 announcement that it wouldn’t allow those states to access three federal child care and family assistance funds:

- Child Care and Development Fund: nearly $2.4 billion to help states support child care for low-income working families

- Temporary Assistance for Needy Families: $7.35 billion to help states fund programs for low-income families, including job assistance and child care

- Social Services Block Grant: $869 million for services including child welfare programs and education and job training for adults

The HHS Administration for Children and Families cited “serious concerns about widespread fraud and misuse of taxpayer dollars in state-administered programs” as its reason for suspending the funding. It will require the five states “to submit a justification and receipt documentation before any federal payment is released.”

California Attorney General Rob Bonta responded that HHS had provided “no factual or legal basis for blocking access to these critical funds and target the five Democratic-led states based solely on unsupported and unfounded allegations of ‘fraud.’”

Local government responses

Along with the Jan. 8 lawsuit, responses from the five states and their cities and counties include:

Minnesota: This state is at the center of the Trump administration’s fraud allegations regarding child care funding. On Dec. 26, an influencer posted a video alleging that some day care centers operated by Somali residents had misappropriated more than $100 million in public funds.

The feds and the state are investigating, and the Minnesota Department of Children, Youth and Families announced in early January that its Office of Inspector General Investigators and the Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension would be doing extra, unannounced compliance checks at child care centers throughout the state.

Sanford said Minnesota is better positioned to weather the funding storm than some states because it earmarks a “significant amount of state dollars for child care subsidy programs that allow low-income families to get a portion of their costs covered.” State dollars are also allowing the Minnesota Child Care Assistance Program to operate as usual, for now.

“State funds are sufficient to support CCAP services for several months while DCYF works to respond to federal requests,” DCYF announced in a Jan. 6 program update.

But local child care operators are worried about what happens after that, Sanford said.

“Profit margins for our child care providers are already so small. For smaller providers, they can be as low as 1% or even nonexistent,” she said. “Labor alone makes up 60 to 70% of child care provider budgets because of state-mandated ratios” of workers to children.

Sanford said local governments are already “distressed by declining amounts of state government aid,” but there are ways to become more resilient when it comes to child care funding.

Sanford said some of Minnesota’s rural communities are working with local employers, counties and school systems to change or suspend zoning laws to allow for child care facilities and to purchase or renovate empty buildings or schools to help offset costs for child care businesses.

Sanford also encouraged local leaders to tell state and federal officials how child care funding cuts directly affect their communities.

“When local governments say, ‘Wow, this is becoming a macro issue,’ that carries a lot of weight,” she said.

Colorado: According to Colorado Attorney General Phil Weiser, the state received $140 million from CCDF and $135 million from TANF in 2025. Weiser said losing that funding would be “devastating.”

“Families would lose access to reliable childcare, forcing parents and caregivers into an impossible choice of either missing work or leaving children in a potentially unsafe environment. Childcare providers would lose essential funding, and even children who do not receive ACF-funded care could lose access if facilities are forced to reduce staff or shut down,” he said in a statement. “Employers would lose valuable workers, hurting states’ economies, and families would lose critical cash assistance to help them afford essentials like gas, groceries and rent.”

Denver’s Child Care Assistance Program stated it is operating as usual but warns users to “budget January benefits carefully” in case there are changes to TANF funding.

The Denver CCAP has also frozen enrollment for new applicants. “This freeze is being enacted as a result of increased program expenses that exceed available funding for the program,” the CCAP stated.

California: Out of the $10 billion in potentially frozen federal funds, about $5 billion is earmarked for California, according to Bonta.

Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass stated the city is working closely with partners at all levels of government to help combat the federal funding freeze. LA’s Community Investment for Families Department is connecting families affected by the cuts with FamilySource Centers for food distribution, utility and rent assistance, Bass said. The city is also partnering with its WorkSource Centers to support low-income workers or people looking for jobs.

Illinois: The Illinois Child Care Assistance Program, which serves more than 150,000 children, receives funding from both the federal and state governments, according to Illinois Action for Children.

“Illinois dollars are continuing to flow, payments are going out and the state is saying not to expect an immediate issue” with child care funding, said Ireta Gasner, vice president of Illinois Policy at the children’s nonprofit Start Early. “But uncertainty and fear are on our organization’s mind and the minds of families throughout the state. There is no local or state substitute for these federal dollars.”

Gasner said local communities can help organizations like Start Early explain the economic impact of child care programs to congressional representatives and the federal administration.

“Municipal leaders are good spokespeople. They want healthy communities, strong local economies and local jobs,” and accessible child care is a key part of that, Gasner said.

She also recommends that civic leaders reach out to their local child care providers. “Understand who these players are,” she said. “Many, many child care programs operate as small businesses, so these disruptions have a quicker or more problematic effect for them.”

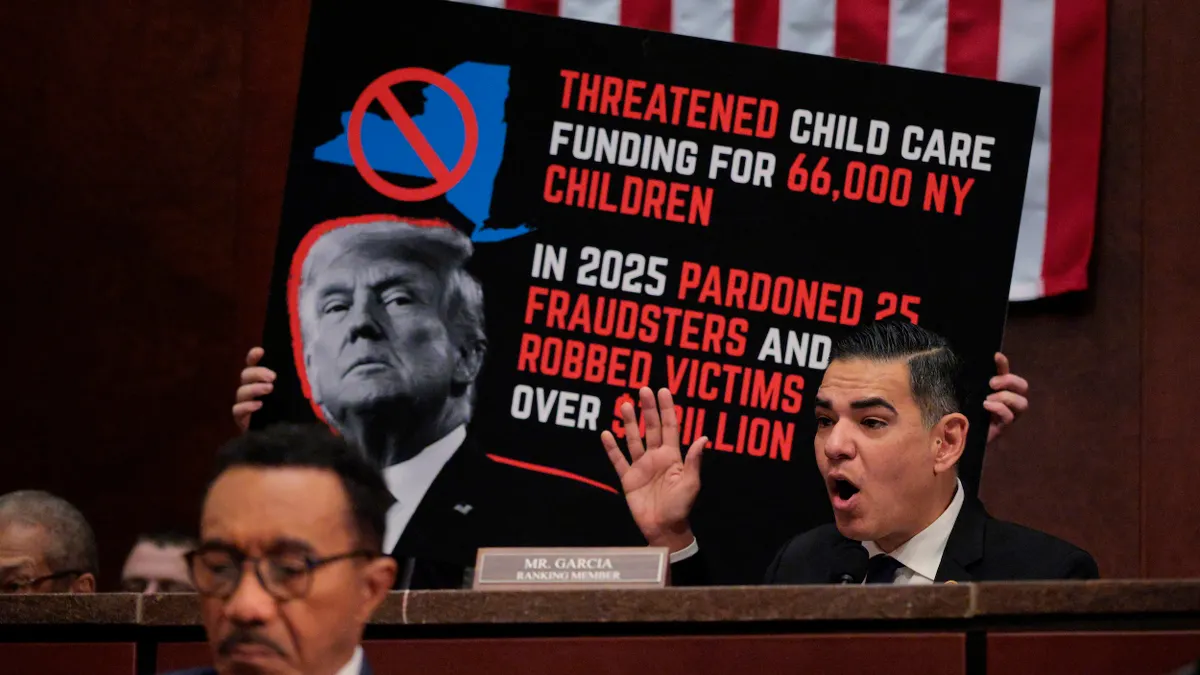

New York: According to the state comptroller, last year the New York State Child Care Assistance Program received more than $1.1 billion in TANF and CCDF funding. In January 2025, more than 95,000 children in New York City benefitted from CCAP services.

The New York State Association of Counties said the state’s counties and New York City will bear the brunt of financing the state CCAP if the federal money doesn’t come through.

“This funding freeze could lead to devastating consequences for innocent children and families who rely on childcare subsidies, local taxpayers and the counties that administer these programs,” said Philip Church, Oswego County administrator and NYSAC president. “While we all support rigorous oversight and fraud prevention, and work hard to ensure taxpayer dollars are used appropriately, a blanket withholding is the wrong approach and will create collateral damage that far exceeds any fraud concerns.”