As officials continue to piece together the events leading up to the catastrophic Independence Day flooding in the Texas Hill Country, the absence of warnings that might have saved lives remains a sore point.

The National Weather Service first issued a flash flood warning for Kerr County just after 1 a.m. on July 4 and updated the warning four more times over the next three hours. It issued a flash flood emergency warning of catastrophic flooding, around 4 a.m., but the warnings never made it to many residents and visitors to the tourist-heavy area, according to meteorologist and former emergency manager Alan Gerard, CEO of Balanced Weather.

“It definitely seems like, for whatever reason, as the warnings were being issued the night of the flash flooding, there was some sort of communication breakdown between what was issued by the National Weather Service and what was getting to the people on the ground in Kerr County,” Gerard said.

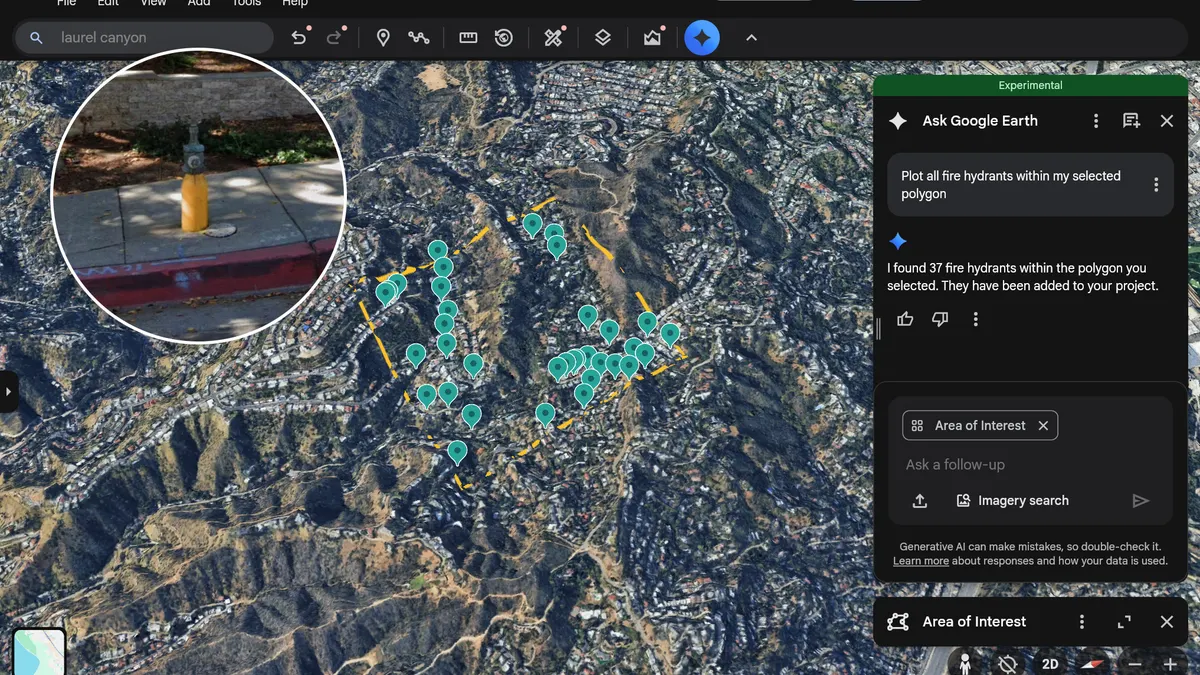

A cluster of unfortunate events — including the loss of a warning coordination meteorologist at the Austin/San Antonio NWS offices to Department of Government Efficiency cuts and the county’s resistance to installing sirens — contributed to the tragedy, but it is not unique to Kerr County. Meteorologists call this inability to control, or even know, how city and county officials are receiving and further dispatching extreme weather warnings the “last mile” problem.

And while residents bear some responsibility for setting themselves up to receive warning information, Gerard said, “there’s a lot that counties and cities can do to help that process and mitigate some of the worst impacts from these types of flood and weather events.”

NWS alerts stalled in Kerr County

The first thing local communities should do, Gerard said, is get certified through the NWS StormReady program, which requires them to establish a 24-hour warning point and emergency operations center, create a system that monitors local weather conditions and have more than one way to receive severe weather warnings and forecasts and alert the public.

“The entity that’s responsible for your city should have two or three different ways to get information,” Gerard said. NOAA weather radio has been a reliable backup, though social media reports this week indicate that NOAA is telling public television stations to remove equipment used for these alerts from their towers because it is not renewing maintenance contracts for them. NWS also runs a Slack channel that local dispatchers and emergency managers can use during weather events, he said.

Kerr County was not StormReady-certified. It did have CodeRED, a private service that sends out emergency notifications via phone and text. Even so, CodeRED warnings did not go out until hours after NWS issued its flash flood emergency, and not all residents received the warnings.

The problem with opt-in systems like CodeRED is that not all residents are aware they exist, said Bob Henson, a meteorologist and science writer who contributes to Yale Climate Connections.

Government officials can send out Wireless Emergency Alerts, which are geographically targeted text messages delivered to mobile phones and don’t require an opt-in subscription. But, Henson said, the proliferation of private warning systems like CodeRED has led to public confusion. “The more systems, the more complicated things can get,” he said.

In addition, many people don’t understand the difference between a watch and a warning, Henson said. The NWS streamlined its hazard messaging system in 2024, but confusion remains. “The landscape has changed enormously in the last 20 years,” he said. “But there’s a lot of hesitation to change the terms that have been used for 70 years for fear of causing additional confusion.”

Warning fatigue and confusion

Warning fatigue is another issue contributing to the last-mile dilemma.

“People aren’t ignoring warnings on purpose,” Texas Sen. Paul Bettencourt, a Republican, wrote in a post about bringing back warning sirens on X. “There are simply too many in a day, and they are turning off their phones at night.”

Because the first warnings in Kerr County were sent hours before the Guadalupe River crested, many people disregarded them, Henson said. And many people are suspicious of the warnings because myths about them have proliferated in the age of social media.

“Obviously, our cell phones are going off for all sorts of things at this point — we’re getting news alerts, EAS alerts, Amber alerts,” Gerard said. “That’s definitely a real concern.”

That’s why public education campaigns and partnerships with community organizations and schools are so important, Gerard said. City and county officials should ensure that vulnerable populations like hospitals, schools and day cares have weather radios and safety plans, he said.

It’s important for Weather Service and emergency managers to build relationships with the public, Gerard said. “There’s no doubt that part of what the Weather Service and the emergency management community is working on to bridge that last-mile gap is building these relationships ahead of time.

Editor's note: We have updated this article to correct the spelling of Bob Henson's name and correct an error in the description of CodeRED.