Dive Brief:

-

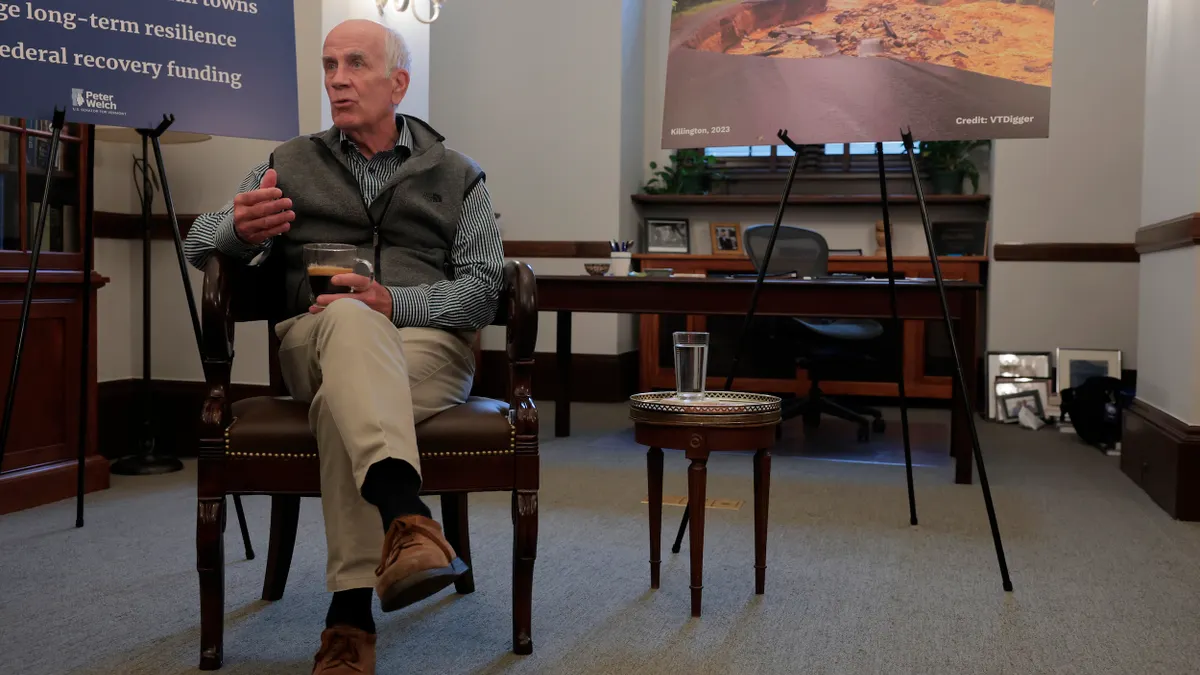

An Urban Institute report released today found that many states lack the resources to take on a greater share of disaster recovery costs if the Trump administration follows through with its plans to shift more emergency management responsibilities to state, local and tribal governments.

-

Of the 31 states that received federal disaster response and recovery resources in 2019, the most recent year with data availability, only five had enough resources set aside in their budgets to cover the cost of disasters, the report found.

-

“With this analysis, we really hope that state leaders, and then local leaders inside those states, can get a better sense of their recent and current fiscal capacity and how that compares to how much was transferred from the federal government to state and local governments,” Sara McTarnaghan, co-lead of the climate and communities practice area at the Urban Institute and one of the report’s authors, told Smart Cities Dive.

Dive Insight:

The Trump administration is considering plans to limit the federal government’s role in paying for disasters by making it harder to qualify for federal disaster assistance, contributing less money to disaster recovery and limiting federal spending on hazard mitigation programs.

“At the core of all this reform is the uncertainty around the potential changes for FEMA,” McTarnaghan said. “The fact that states and localities don’t actually know what might happen if their governor submits a request for a presidential disaster declaration is a huge issue.”

While state leaders and emergency management professionals generally agree that shifting more responsibility to state and local governments will give them “clearer incentives to reduce the ballooning cost of disasters and invest in disaster resilience,” according to the report, “states would need to identify own-source revenue to cover costs or face a more prolonged, incomplete recovery, with significant well-being and economic implications for communities.”

Some states have created disaster-specific funds or increased contributions to existing ones, while others have had to draw down those funds to cover immediate needs. Florida’s Emergency Preparedness and Response Fund, established in 2022, is slated to be terminated in 2026, while California’s disaster-response funding has been diminished by multiple high-cost disasters, the report states.

States that didn’t set aside sufficient funds to cover disasters would have had to come up with an average of $37.9 million if federal aid had not been available in 2019. That year, North Carolina would have faced a $46 million shortfall after Hurricane Dorian and Tropical Storm Michael without the $100 million in FEMA resources it received.

“Our analysis indicates losing FEMA funding would be especially hard on states at high risk of disasters and with low fiscal capacity, such as Louisiana and North Carolina,” the report states.

Some states have had to pay for disasters using rainy day funds, which are designed to cover revenue shortfalls during unexpected economic downturns, according to the report. All but four states have such funds, which range from $240 million in South Dakota to more than $20 billion in Texas.

Local governments have their own rainy day funds as well, Lucy Dadayan, principal research associate with the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center’s tax and income supports division at the Urban Institute, said. “And now that FEMA funding is under question, it’s time to think about having dedicated disaster management funds at a local level to be able to protect your community.”