A wave of guaranteed income pilot programs launched in cities throughout the U.S. over the past five years has been effective in addressing basic needs such as housing and food and improving mental health, but their impact on long-term financial security is less clear, according to experts and program administrators.

The number of cities that have launched guaranteed income pilot programs, which provide certain residents with no-strings-attached monthly cash payments, has exploded since Stockton, California, launched the first one in 2019. More than 150 cities have some type of guaranteed income program today, said Sukhi Samra, director of advocacy group Mayors for a Guaranteed Income.

Many of those programs launched shortly after mayors saw how federal economic impact payments included in COVID relief packages affected millions of Americans, said Mary Bogle, principal research associate at the Urban Institute.

Several reports and studies evaluating the effectiveness of now-completed pilot programs have recently been published.

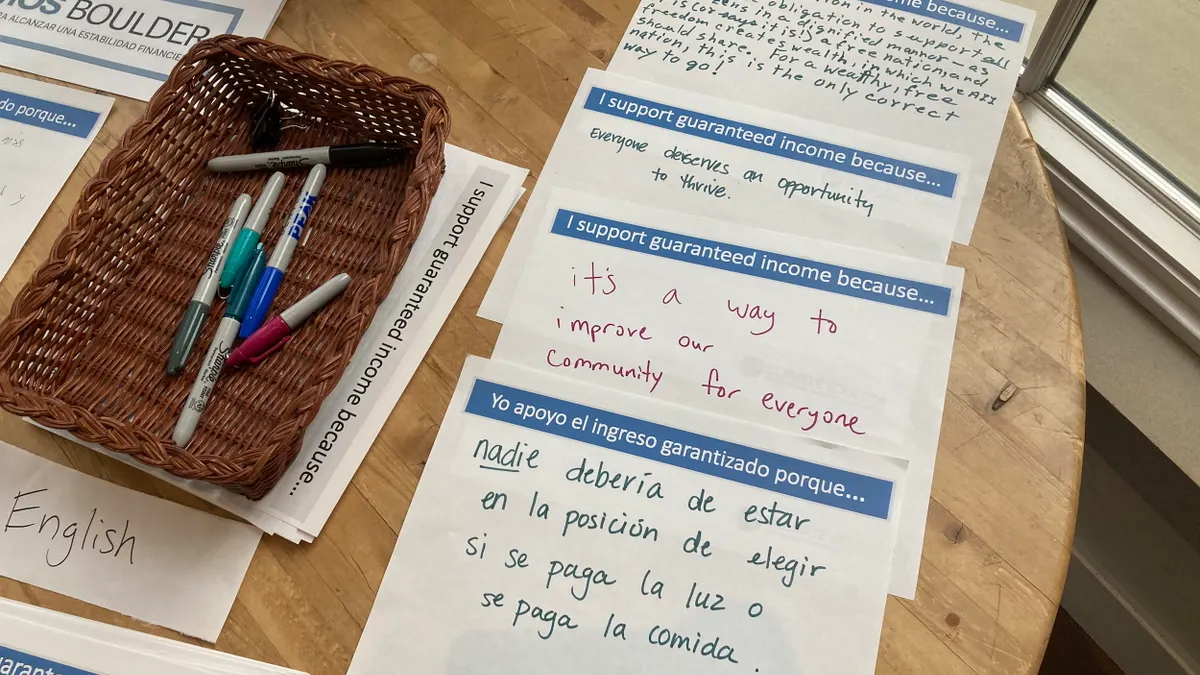

Boulder, Colorado, reported that its 2023 pilot program — which gave 200 residents facing extreme poverty $500 per month over two years — did not have a clear effect on recipients’ employment status. That means it did not necessarily help them achieve long-term financial security, according to a city-funded report. It also didn’t make a meaningful difference in recipients’ ability to pay for healthcare, child care and transportation.

Regardless, the direct payments’ impact on recipients was “significant and fast,” said Elizabeth Crowe, deputy director of Boulder’s Housing and Human Services Department.

Nearly one-third of recipients sought additional education or training during the course of the pilot, and the program helped recipients purchase food, cover housing and utility costs, and pay down debt, the report stated.

With their basic needs met, program participants were able to relax a little instead of worrying about how they were going to feed their family or pay their rent, said Crowe. They could spend more time with their children and in supportive work and social environments because they were able to get rid of an extra gig job, she said.

The program showed that people with less money “can be trusted to make really good decisions for themselves and their family that lead to their ability to meet basic needs and get ahead,” Crowe said.

“A good use of our money”

Many cities — navigating post-pandemic spikes in homelessness and evictions — have used federal funding they received from the 2021 American Rescue Plan Act to set up guaranteed income programs that help cover household budget gaps, Bogle said.

The mayors of these cities saw that the lives of some low- to middle-income people improved during the pandemic because the extra income boost from federal economic security payments allowed them to stay home with their children, she said.

That led some mayors to believe that guaranteed income programs were “a good use of our money because we know our citizens suffer when they don’t have basic income,” she said.

Boulder’s guaranteed income program showed that people with less money “can be trusted to make really good decisions for themselves and their family that lead to their ability to meet basic needs and get ahead.”

Elizabeth Crowe

Deputy Director, Boulder Housing and Human Services Department

Programs were launched in large and small communities including Austin, Texas; Evanston, Illinois; Louisville, Kentucky; and Los Angeles County. Each city and county established its own process for determining who would receive funds, said Samra.

Some cities targeted residents based on the area median income, accepting residents who are not considered impoverished and thus might be ineligible for other federal assistance, but they still struggle because of the high cost of living in their community, Samra said. Other cities provided benefits to specific vulnerable populations, such as single parents and caregivers, youths transitioning out of foster care, and domestic violence survivors, she said.

Birmingham, Alabama’s program, for example, targets single mothers, said Samra. Santa Fe, New Mexico’s program provides benefits to community college students; Gainesville, Florida, targets people who have been incarcerated.

Generally, the monthly payments range from $500 to $1,000, although some have been as low as $300, Bogle said. They most often last for one or two years, she said.

In total, an estimated 35% of guaranteed income program cash payments was spent on retail sales and services, 32% on food and groceries, and 9% to cover housing, utilities and transportation, according to research by the Mayors for a Guaranteed Income, the University of Pennsylvania and Stanford University.

Several Republican-led states, including Iowa and Texas, have banned or are attempting to ban cities from launching guaranteed income programs, arguing they make people dependent on the government.

Still, following the success of their guaranteed income programs’ initial launches, some cities are continuing and even expanding them. Richmond, Virginia; Tacoma, Washington; and Madison, Wisconsin, are among the cities that have extended their programs beyond their initial cohorts of recipients.

This November, Cook County, Illinois, became the first U.S. county to establish permanent funding for guaranteed income, following the success of its $42 million pilot, which provided $500 monthly payments to more than 3,000 residents over two years.

Overall, guaranteed income program participants have been “more likely to find long-term employment, further their education and increase the economic security of their households,” said Samra. “Not a single pilot has shown a decrease in employment.”

“A better part of this community”

In Minneapolis, the 200 low-income residents who received $500 monthly payments over two years through a pilot program were able to address immediate needs such as food, housing and utilities and pay down debt, add to their savings and improve mental health, said Mark Brinda, manager of workforce development for the city.

“In the short run, we did see that some of these immediate needs were being met with pretty good effectiveness,” said Brinda.

But the program didn’t improve the labor supply, according to a report from the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, which reviewed the pilot’s impact.

An additional $500 per month over the course of two years did not necessarily catapult recipients into job training or a new career because participants tended to address their immediate needs first, said Brinda.

That raises questions, he said. How long would someone need to receive the payments until they are stable enough to invest in education and training or move into a higher-paying job? What kind of long-term impact would payments extending beyond two years have had on participants?

“The move out of that job into a different job with maybe higher pay might, in fact, be a longer-term process, similar to buying a home,” said Brinda.

In some cases, cities have seen slight dips in job attainment or hours worked during the first year of a guaranteed income program, said Bogle. Some people dumped additional gig jobs after receiving the checks. But that’s not necessarily a bad thing, she added.

Any expectation that programs like the ones in Minneapolis and Boulder should lead to long-term economic stability is not realistic, said Bogle.

When people are behind, they use the money to pay off their debt, including arrears on their rent, and to pay for basic needs such as food, including balanced meals. Some use the economic stability created by the program to spend more time with their children or take time off to pursue additional job training, she said.

Neither Minneapolis or Boulder has immediate plans to continue the programs. Both programs had budgets of $3 million, funded mainly through ARPA.

According to Crowe, Boulder is actively fundraising to continue the program, perhaps at a smaller scale. The program achieved success because it brought dignity and trust, elements that government programs requiring people to continuously prove their poverty lack, she said.

Recipients felt “like they are a better part of this community,” said Crowe. “They want to stay living here … they feel seen, they feel heard, they feel supported in a way that most government programs don't.”