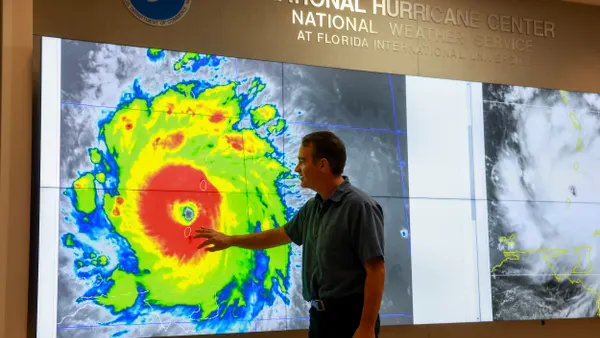

Local emergency managers are girding for the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s shutdown tomorrow after lawmakers in the House and Senate were unable to negotiate a compromise over Democrats’ demands that the Department of Homeland Security place restrictions on federal immigration enforcement officers.

For emergency managers who are already dealing with slower, less predictable payment processing and response time from the pared-down agency, “this shutdown just adds a lot of unnecessary stress and uncertainty to the everyday process,” said Andrew Rumbach, senior fellow and colead, climate and communities for the Urban Institute.

“What the shutdown does is it just starts to kick stuff down the road,” said Tom Sivak, a former FEMA regional administrator. “Funding reimbursements, distribution of grant money, investment justifications — all these things just back up right to the local emergency manager.”

FEMA will “continue carrying out its lifesaving mission for supporting disaster-response efforts” during the shutdown, Gregg Phillips, associate administrator for the agency’s Office of Response and Recovery, told the House Appropriations Subcommittee on Homeland Security during a Wednesday hearing. FEMA’s Disaster Relief Fund has enough money to continue emergency response activities for the foreseeable future, he said, but it will be “seriously strained” if a catastrophic disaster occurs.

A lapse in appropriations due to the shutdown will “severely disrupt FEMA’s ability to reimburse states for disaster relief costs and to support recovery from disasters” and cause many FEMA employees to be furloughed, “limiting the agency’s ability to coordinate effectively with state, local, tribal and territorial partners,” Phillips said.

Long-term planning and coordination will be “irrevocably impacted,” and first responder training will be significantly disrupted, he added. “The importance of these trainings cannot be measured, and their absence will be felt in our local communities.”

Exacerbating uncertainty

Tomorrow’s shutdown is an acute crisis in a year of chronic uncertainty for local officials who work with FEMA. Since President Donald Trump signed an executive order in March 2025 shifting more responsibility for disaster preparedness to state and local governments, his administration’s efforts to reshape FEMA — including staff cuts, canceled resilience programs, higher disaster thresholds and attempts to tie funding to immigration enforcement — have left the agency’s resources stretched thin and made federal support less predictable.

“2025 was really an inflection point,” said Sara Labowitz, a senior fellow in the sustainability, climate and geopolitics program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “States and counties and local governments have been used to FEMA being pretty responsive, but what we’re seeing now is a chaotic policy environment. There’s less money, and while there’s still money flowing in the system, it’s much less predictable and reliable than it was a year ago.”

The shutdown will exacerbate the uncertainty and disruption local emergency managers were already dealing with, Rumbach said.

“FEMA’s primary function, in a lot of ways, is to move money,” he said. “The moving of money requires a lot of paperwork and requires a lot of people’s eyeballs and signatures. When those people are not able to work, a lot of that comes to a stop. So, it affects someone who’s just had a disaster today as much as it affects someone who had a disaster two years ago and is waiting for reimbursements.”

As emergency managers have waited for grant money to be released and FEMA’s status as an agency to be decided, they’ve continued to build preparedness and focus on trainings and exercises, Sivak said.

“The challenge of what’s next continues to come into play,” he said. “We’re adapting to the fact that there are going to be continuous shutdowns, and emergency managers are adapting to the new norm of what that looks like.”

Long-term challenges

The shutdown is yet another indicator that local governments need to shift away from FEMA toward locally led disaster mitigation, Labowitz said.

“I’ve heard anecdotally from people that they are planning for fewer federal resources to flow into the system, but I don’t know that anybody has a fully baked plan to fill the gap from where we have been to the new policy environment,” she said.

With mandates to balance their budgets, local and state governments are reconsidering revenue sources and spending. But the process takes time and planning, Labowitz said, “and the way that the policymaking has unfolded in the last year really hasn’t given them the opportunity to do that.”

“I don’t think most emergency managers are able to say, ‘Oh, we’re going to start putting aside funding for a rainy day fund,’” Rumbach said. “Most of them are relying on external money coming to them, and it’s not as though they have a lot of discretion over how they do their budgets and structure things.”

For local emergency managers who were already struggling with budgets, educating elected officials and the public about the value of their efforts is more imperative than ever, Sivak said. The shutdown presents another opportunity to focus on how local investments in disaster mitigation will yield payoffs in preparedness and resilience, he said.

“While we’re dealing with the immediate challenge of yet another shutdown, what we really have to be thinking about is, what are these long-term challenges going to look like in the next year, three years and five years down the road?” he said.

As shutdowns and resource shortages become a fact of life, Sivak said, emergency managers must seek more innovative solutions to accelerate capacity and build preparedness without adding staff or funding.

“The more we educate ourselves, the better informed we all are to focus on what matters most, which is people,” he said.

For Kathy Fulton, executive director of the American Logistics Aid Network, a nonprofit that provides supply chain assistance during disasters, that’s where the rubber meets the road.

“Sometimes we get so wrapped up in policy and spending that we forget the reason we’re doing this is that somebody at the other end is about to have the worst day of their life,” she said. “So, what can I do now to make sure that even if I can’t stop the disaster from happening, I can help ease their pain?”